8 Design-Forward Museums in Helsinki for Architecture Lovers

This article presents eight architecturally impressive museums in Helsinki and explores how different periods of construction, renovations, and design approaches shape the city's architectural identity. The focus is on the museums' architecture and their role in the urban landscape. This piece was created in collaboration with an engaged reader of this website.

Covered in the Article

Helsinki offers museums that impress not only with their collections but also with their architecture. Over the decades, the Finnish capital has developed a museum landscape that unites different styles and eras. The spectrum ranges from underground galleries to neoclassical villas.

If you are interested in architecture, Helsinki’s museums offer more than artworks and historical objects. The buildings themselves tell stories about urban development, design choices, and Finland’s approach to architectural heritage. This article presents eight museums that are particularly interesting architecturally and explains what their design reveals about Helsinki.

Why Helsinki Is Especially Interesting for Architecture Lovers

Helsinki often surprises people who care about architecture. While other Nordic capitals score with spectacular one-off landmarks, the Finnish metropolis excels with a different idea: a carefully composed whole.

The city combines Nordic modernity with functionalist principles that still shape the urban landscape today. Architects such as Alvar Aalto turned Helsinki into a laboratory for organic design, where buildings merge with their surroundings. This design philosophy spans all eras and appears in public buildings and residential districts alike.

Helsinki’s handling of contrasts is particularly noteworthy. Art Nouveau buildings from the period of Russian rule stand next to sober post-war structures and contemporary interventions. This mix never feels random but follows a clear design logic. The city shows how different architectural languages can enter into dialogue.

Another source of fascination lies in Finnish material culture. Wood, granite, and copper are not treated as mere building materials but as carriers of meaning. Northern light plays a central role: during the long winter months, interiors become staged light spaces that make the architecture tangible.

Helsinki’s museum scene concentrates this architectural variety. Here you can see how the city handles its built heritage while integrating contemporary ideas. For architecture lovers, the museums offer more than galleries: they are built manifestos of a distinctly Finnish understanding of space, material, and function.

8 Architecturally Impressive Museums in Helsinki

Helsinki’s museum landscape is as diverse as it is considered. The following eight institutions showcase different approaches to space, light, and urban integration. The spectrum presented here ranges from underground galleries to functionalist icons. Each museum tells its own architectural story about Helsinki’s design identity.

Amos Rex

Amos Rex opened in 2018 and ranks among Helsinki’s most unusual museum projects. The galleries lie entirely beneath Lasipalatsi Square, while only curved concrete skylights are visible at the surface. These domes define the square and also serve as play areas.

The architects JKMM integrated the historic 1930s Lasipalatsi as the entrance. Below ground, generous, column-free spaces open up, lit by daylight from above. The solution marries preservation with contemporary museum architecture and creates additional public space in the city.

Kiasma – Museum of Contemporary Art (Nykytaiteen museo)

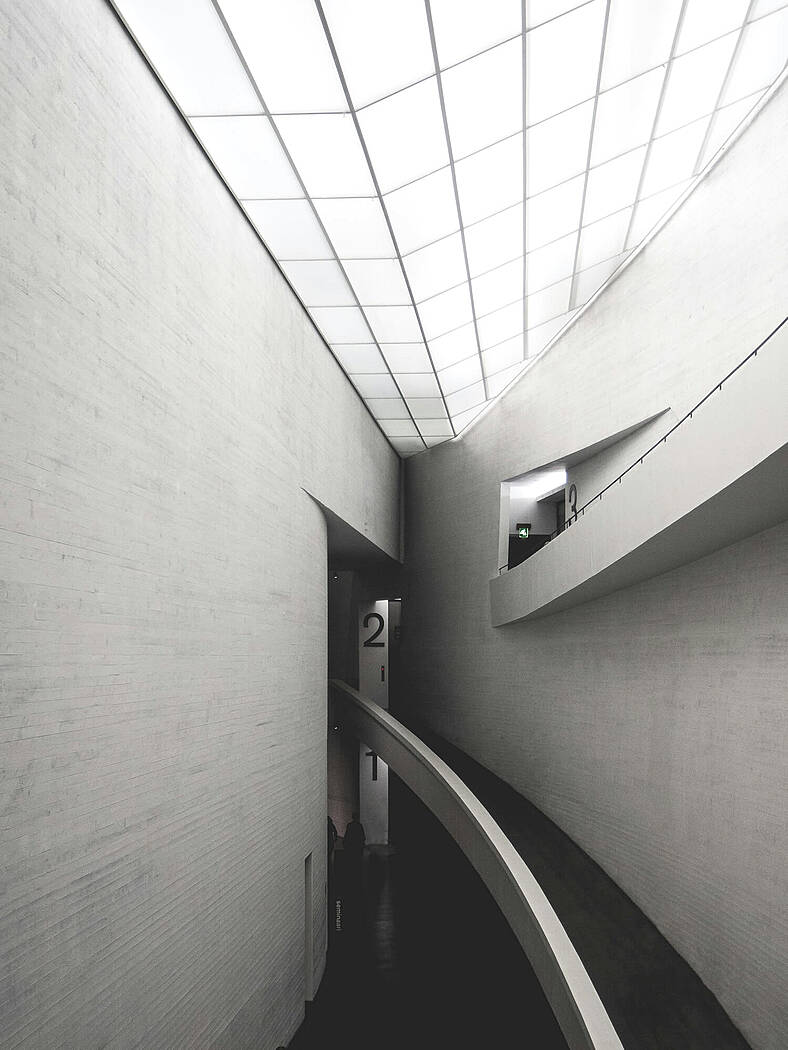

Kiasma opened in 1998, designed by American architect Steven Holl. The concept follows the principle of interweaving: two spatial bodies penetrate each other to form a flowing shape. The building stands opposite the Finnish Parliament and deliberately contrasts with the rectilinear surroundings.

The facade combines light plaster, metal, and expansive glazing. Inside, skylights positioned in various configurations create shifting light moods across flexible exhibition spaces. Controversial at its opening, Kiasma is now considered an integral part of the cityscape.

Helsinki City Museum (Helsingin kaupunginmuseo)

The Helsinki City Museum occupies a cluster of buildings from different eras on Aleksanterinkatu. The oldest part dates to the 18th century and was originally a residence. Later additions and conversions turned the museum into an architectural palimpsest that also makes Helsinki’s urban history legible in built form.

The galleries are spread across several connected buildings. Historic timber ceilings meet modern interventions, and narrow staircases lead into generous halls. This spatial variety mirrors the museum’s curatorial approach: Helsinki appears as a grown city whose layers remain visible.

Ateneum Art Museum (Ateneumin taidemuseo)

Completed in 1887, the Ateneum is one of Helsinki’s key examples of Neo-Renaissance architecture. Architect Theodor Höijer drew on the classical museum buildings of Central Europe. The symmetrical facade with columns and a central pediment gives the building a commanding presence on Rautatientori. It makes it one of the city’s most popular photo spots in the city.

Inside, a broad main staircase leads to galleries arranged around a central light court. The lofty, skylit rooms reflect late 19th-century ideas of museum architecture. Later renovations preserved the historic fabric while integrating modern standards for climate control and lighting.

Design Museum Helsinki (Designmuseo)

The Design Museum occupies a former school building from 1894. Architect Gustav Nyström originally designed the neo-Gothic brick structure as a school of applied arts. The distinctive facade with pointed-arch windows and gables still defines the streetscape in Kaartinkaupunki.

The conversion into a museum took place as early as 1978. The original classrooms were transformed into exhibition spaces, largely preserving the historic layout. The building combines industrial materiality with handcrafted detailing, providing a fitting backdrop for Finnish design.

Sinebrychoff Art Museum (Sinebrychoffin taidemuseo)

The Sinebrychoff Art Museum occupies an 1842 villa that originally belonged to the Russian-Finnish brewing family Sinebrychoff. The Empire-style building in Punavuori reflects the domestic culture of the 19th-century bourgeoisie. The yellow facade with white pilasters lends the house a classically elegant presence.

The interiors are largely preserved in their original state. Stucco, parquet floors, and historic furniture set the scene for the collection of European Old Masters. The museum serves as both an art venue and a cultural monument. Its intimate proportions differ markedly from the expansive halls of more modern museums.

Didrichsen Art Museum

The Didrichsen Art Museum sits on the Kuusisaari peninsula and was completed in 1965 as a private home with an integrated gallery. Architects Viljo Revell and Keijo Petäjä designed it for the collector couple Marie-Louise and Gunnar Didrichsen. The modernist villa blends into the wooded landscape and uses the slope to frame generous views over the bay.

Extensive glazing connects inside and out, while natural stone and wood define the material palette. The galleries unfold as a sequence of differently proportioned rooms that allow intimate encounters with the artworks. Later extensions increased the exhibition area without altering the character of the original design.

Tram Museum (Ratikkamuseo)

The tram museum is housed in a former depot from 1900 in the Töölö district. The brick building with its functional articulation originally served as a workshop and storage hall for Helsinki’s trams. The tall nave-like halls with their steel roof structures are typical of turn-of-the-century industrial architecture.

The conversion into a museum took place in the 1990s. The original spatial structure was retained, and the tracks inside were integrated into the exhibition. The building showcases industrial architecture in its pared-back form and provides an authentic setting for the history of public transport. If you are interested in today’s transport system in Finland, you will find practical information on trams, buses, and other modes in this guide.

What These Museums Reveal About Helsinki’s Approach to Architecture

The eight museums presented here show more than just different styles. They reveal a specific understanding of how architecture should work in the city. Helsinki does not rely on spectacular gestures but on integration and continuity. This attitude shapes the museum landscape and sets it apart from other European capitals.

Restrained Architecture as a Deliberate Choice

Many Helsinki museums do not stand out through extreme forms or monumental gestures. Amos Rex largely disappears underground, the Design Museum occupies a former school, and the Sinebrychoff Museum remains a villa. This restraint is not a design weakness but a conscious strategy.

Finnish architecture traditionally follows the principle of appropriateness. Buildings should respect their context and fit into existing structures. This stance has historical roots: Finland long had to assert its national identity in the face of dominant neighbours. Architecture became a means to express independence without provocation. The museums show that this tradition persists to this day.

Adaptive Reuse as a Design Strength

Strikingly, many museums in Helsinki emerged from the reuse of existing buildings. The City Museum uses historic houses; the Tram Museum uses a former depot; the Design Museum uses a former school. This practice is not only economically motivated but also reflects a design philosophy.

Conversions force architects into dialogue with the existing fabric. They must mediate between preservation and intervention, between historical identity and contemporary requirements. Helsinki has developed real expertise in this. The city shows that new builds are not always the most interesting solution. Sometimes the most convincing spatial qualities arise precisely from the tension between old and new.

Why Museum Architecture in Helsinki Often Feels Quieter

Compared with other capitals, Helsinki’s museums seem less showy. There are no iconic stand-alone buildings like the Guggenheim museums or the Centre Pompidou. Even Kiasma, criticised at its opening as too dominant, now fits naturally into the cityscape.

This "quiet" architecture has to do with the Finnish understanding of the public realm. Museums are not seen as monuments but as accessible places within the urban fabric. They should invite rather than intimidate.

The Nordic tradition of modesty plays a role, as do pragmatic considerations: in a relatively small city, too many architectural statements would upset the balance. Helsinki shows that restraint can be a form of strength.

Museums as a Key to Helsinki’s Architectural Identity

Helsinki’s museum landscape offers a clear view of how the city approaches architecture. Each institution represented represents a different time or style. Together, they provide an overview of the role architecture plays in the Finnish capital.

All of these museums share one thing: they prioritise practical solutions over flashy forms. In Helsinki, buildings are meant to work well and suit their surroundings. Standout landmarks are rarer, but thoughtful overall compositions are common.

The museums, therefore, offer visitors more than just exhibitions. They show how Helsinki handles old buildings and where new architecture is emerging. If you want to discover more museums in Helsinki, you will find additional venues with different architectural approaches in the HelsinkiTipps travel guide.Through its museums, Helsinki shows that restrained architecture can be just as compelling. The city blends historic buildings with contemporary structures to create a varied urban landscape. The museums are a good starting point for understanding this mix.